Power – and its potential for transformation and compassion - resides at the heart of the story of Exodus. In a dramatic moment, Moses leads the oppressed Jewish people out of slavery in Egypt, only to be halted by the seemingly impenetrable Red Sea. Then, the power: the Red Sea parts, and the Jews walk toward their freedom and self-determination. As autonomous people, the Jews are transformed by this power, and also they are implored to embrace compassion, when God reminds the angels that the Egyptians “are God’s children” too.

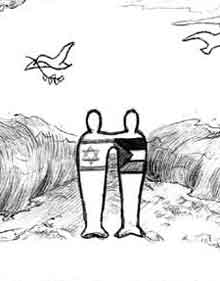

Today, Jews must part a modern Red Sea – the psychosocial fear, anger, and mistrust that divides Palestinians and Israelis – to claim a different kind of freedom, one of communal reconciliation and cooperation for life sustenance.

If we are to take the parting of the sea as a metaphor in the context of an oppressed people’s struggle for freedom, then maybe our inquiry into its applicability to today’s challenge could engage the questions of power, transformation, and compassion. What is the power symbolized by the parting of the red sea? What does this power make possible?

The Three Faces of Power

Imagine it: The sea stretches in infinity before you. One wave so strong it could pick you up and carry you like a twig to shore. An undertow so powerful it could drag you to the depths, helpless and drowning. Your mortal strength seems powerless against the currents and tides. What force could possibly “part the sea?” What force could bring about freedom for an oppressed people? What force could facilitate reconciliation in a seemingly “intractable” conflict? What is that power?

Peace researcher Kenneth Boulding talks about the “three faces of power” – threat power, exchange power, and integrative power. He defines each as follows:

- Threat power: “You do something I want you to do, or I’ll do something to you that you don’t want me to do.”

- Exchange power: “I do something you want me to do, and in return you do something I want you to do.”

- Integrative power: “I do something authentic (from my heart), and in the process, I have faith that we will end up closer in our relations.”

Many of us are familiar with threat power – it’s dramatized in violent Hollywood movies, enacted by armies and police forces, and studied at the military science and political science departments of Universities. We are also familiar with exchange power – it resides in our wallets, drives the world’s economy, and is studied at economics and business schools. Integrative power, to say the least, is less well understood.

Could threat power or exchange power “part the sea”? What power could bring about the kind of reconciliation that would enable long-term healing and cooperation between Israelis and Palestinians? If integrative power is the one at work here – and the one we need to harness right now - let’s examine how this kind of power has operated in other modern freedom struggles.

Gandhi and Integrative Power

In May of 1893, a young Indian attorney named Mohandas K. Gandhi was ejected from a train in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa for one reason: he was not white. Though holding a first-class ticket, the train operators decided he was not fit to occupy a first-class cabin seat, based solely on his skin color. Gandhi made a decision that changed his life, and history. He decided to transmute his anger, remove all hint of vengeance or reprisal, and positively approach this insult as one against all humanity. He concluded that all parties involved were demeaned by this unjust situation. He set out to free oppressed and oppressor alike from the structure of violence. Gandhi converted a negative drive of anger and resentment into a positive drive of universal love and determination for social justice. In the process, he unleashed an indescribable power inside himself. This personal conversion of a negative drive into a positive drive is precisely what the sea’s parting symbolizes – the power unleashed by an individual’s spiritual love, a source of limitless strength. This is the “greatest power [humans] have been endowed with.” If the sea is a barrier, the parting of the sea can be seen as our personal ability to surmount the most difficult obstacle when we unleash an internal positive drive. Gandhi said of this conversion, “I have learnt through bitter experience the one supreme lesson to conserve my anger, and as heat conserved is transmuted into energy, even so our anger controlled can be transmuted into a power which can move the world.”

and in the process, I have faith that we will end up closer in our relations.”

Gandhi made it his mission in life to right the wrong utilizing integrative power. Thus began a 40-year freedom struggle for Indian civil rights in South Africa and home rule in India. Gandhi’s movement involved dialogue, self-sacrifice, constructive work to rebuild India’s indigenous economy and cultural civilization, and willingness to nonviolently oppose injustice – always with an eye to an integrative process and outcome. Gandhi’s steadfast commitment to right means and right ends, and the ultimate goal of friendship with the oppressors, is reflected by British historian Arnold Toynbee’s comment, “Gandhi made it impossible for us to go on ruling India, but he made it possible to leave with dignity.” Indeed, Gandhi and his followers had done something authentic, and moved closer in relations with the British.

In addition, the parting of the Red Sea demonstrates what becomes possible when a negative drive is converted to a positive drive. To India’s numerous “realist skeptics,” Gandhi’s plans to use integrative power to usher out the British as friends seemed about as plausible as parting the Red Sea! To one skeptic who said, “You know nothing of history; this can not be done,” Gandhi’s response was, “You know nothing of history. Just because it has never happened does not mean it is not possible.” Of course, now history demonstrates that integrative power can bring about mass social change and freedom for both oppressed and oppressor. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is a second example: his conversion of anger against white supremacy and segregation to a positive dream for white, black, Jewish, Christian, and Native American fellowship inspired a nation.

What do Gandhi’s and King’s struggles have to do with Judaism, and today’s “Red Sea”? The answer is that these ocular demonstrations of actual integrative power can both inform our understanding of the biblical metaphor and the moral lessons we derive for approaching today’s conflicts.

“They Are My Children Too”

After the sea is parted and the Jews successfully cross over the dry seabed to freedom, the pursuing Egyptian army is swallowed whole and drowned. This event seems to offer no positive metaphorical implications for Gandhi’s or King’s movements, both of which intentionally sought to love, free, and befriend oppressors, never to harm. (When India suffered an atrocity of outright mass murder by British soldiers at Jallianwala Bagh, Gandhi’s approach was conciliatory, even to the perpetrator of the killing: “What General Dyer did we may all do if we had his irresponsibility and opportunity. To err is human and it must be held to be equally human to forgive if we though being fallible would like rather to be forgiven than punished and reminded of our misdeed.”) Gandhi clearly believed in separating the oppressor from their agenda by opposing the unjust actions but not hating the people who carried out the actions. Retributive violence is not a sustainable, integrative approach to our problems.

The next part of the story has significant implications. According to Talmud, as the angels began rejoicing when the Egyptians were drowned, God said, “My children are sinking in the sea, and you sing songs?” Here, God is stating that all humans are of equal worth; none is more precious than the other. Gandhi worked tirelessly for social justice, promoting uplift and equal rights for the oppressed classes of India. Previously known as “untouchables,” he called them “Harijans,” or “children of God,” and promoted alleviation of their oppression which in many ways was comparable to the social stigma African-Americans faced in Dr. King’s day. Gandhi also sought fellowship between persons of all faiths, and said, “I am a believer in the truth of all the great religions of the world. There will be no lasting peace on Earth unless we learn not merely to tolerate but even to respect the other faiths as our own…. I am a Hindu. I am a Muslim. I am a Jew. I am a Christian. I am, after all, a human being, and I am connected to all my fellow human beings!”

We Are All Chosen

So the three main lessons we can derive from the parting of the sea are: 1) conversion of a negative drive to a positive drive unleashes an individual’s greatest power, 2) when this power is born, the unimaginable becomes possible, 3) all human beings are of equal worth in the eyes of God. All three of these lessons were demonstrated in the persons of Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. – their words, their actions, and their movements. Centering our approach in both recent historical success stories of integrative power, and our highest moral vision, how can we part today’s “Red Sea”: heal the Holy Land and transform the Palestinian/Israeli conflict?

First point: conversion of a negative drive to a positive drive begins in the individual. Thus, we who are parties to this conflict – Israelis, Palestinians, the diaspora – can make individual decisions to convert our anger at the injustice we see every day into a positive drive to heal the wounds, love one another, and seek the humanity in each other. We can be angry at the structures that cause pain, but offer love and dignity to the people, including and especially those who drive the structures.

Some might ask: How does an individual decision matter in such a vast social problem? We might study Gandhi’s movement and note that, while millions of Indians followed Gandhi during the “high points,” at times the movement shrank to only 40 or so of his most committed colleagues. What this means is that the dedication level of each individual might have been the crucial factor in history’s most powerful Empire leaving India on cordial terms. Without the 40, what would have happened?

peace with each other and to demonstrate to the world the power of love to heal conflict?

Second, we can draw upon past real-world examples to envision a radical transformation, both in the process and the outcome. Gandhi set out to do something so radical that few could even imagine it.

Just like the skeptics who doubted Gandhi’s plans to escort the British out as friends, some might believe Israelis and Palestinians cannot be friends. We can only answer that Israeli/Palestinian communal reconciliation is possible, and inevitable when the idea begins to gain traction in the minds of people. Gandhi’s manifesto “Hind Swaraj” (or “Indian Home Rule”) had a catalyzing effect on India, and a serious peace manifesto (“The Integrated People of the Holy Land” perhaps?), supported by dedicated individuals (see point one) could lead to a transformational process and outcome. Non-Governmental Organizations who specialize in processes of reconciliation could be available when those “dedicated individuals” help mobilize a pro-reconciliation movement.

Third, can those of us who are Jewish be courageous enough to expand our ideas of “chosenness” into a new egalitarian peacemaking vision? If we are to believe in the truth of Gandhi’s and King’s work for human equality, then we might ask ourselves, how can we create a collaborative process and outcome where every Palestinian and Israeli is equally valued? How can we transform our thinking from “we are chosen” to “we are all chosen?”

What if we were to believe that Palestinians and Israelis have been chosen to make peace with each other and to demonstrate to the world the power of love to heal conflict? We cannot erase the past; we can transform the present and build a future together. While some might see the world as it is now, our vision, like Gandhi’s and King’s, can be one of the world as it should be. For this, in fact, is what the unpronouncable Hebrew word for God literally means: God as God was, as God is now, and as God will be, in the best way God can be.

If we are to walk through today’s Red Sea – together, arm in arm, sisters and brothers – what kind of personal power do we each need to harness?