“Peace in Richmond! We’re in the headlines and on the internet!” exclaimed Robert Brown as he proudly welcomed incoming visitors to join the children, adults and elders already gathered around the fire at the corner of 41st and Cutting in a notoriously crime-ridden neighborhood. Brown, president of the local neighborhood council, is a co-founder of the Tent City peace camps: a homegrown, nonviolent response to the escalating homicide rate in Richmond, California. The media routinely report acts of violence in Richmond, but not this time. Those assembled affirmed the psychic shift unfolding as people found the courage to confront fear and despair with loving presence.

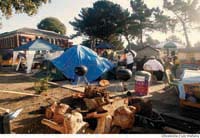

When there was a shooting at the funeral of a murder victim in late September, 2006, the neighbors said “Enough is enough”. A small group of people, spearheaded by Reverend Andre Shumake and Reverend Charles Newsom, began a round-the-clock vigil at 4th and Macdonald in Richmond’s Iron Triangle. Their numbers grew, tents were pitched, and food was donated. A few days later, Tent City #2 was born at Kelsey and Gertrude Streets in North Richmond—a poverty-stricken enclave on the other side of the railroad tracks—under the leadership of wheelchair-bound Garland Harper, whose 22-year-old son Benard Harper II was killed 6 months by gun violence. In a community where physical weakness is often seen as a reflection of inferiority, and the mere thought of peace action amidst a background of turf battles might have provoked scorn and derision, Harper is now shown the respect reminiscent of a minister presiding over his congregation.

Within a week, the call came out to do something on Richmond’s south side, and before long, Robert Brown, James Cash and others had the 41st and Cutting site up and running. On the lower south side of the city, at Marina Way and Cutting, the fourth Tent City came into being. Patrice Boykin, a 39-year old mother, founded this site with encouragement from her neighbors and family to. The men and women who assist Boykin with day-to-day logistics honor her as if she were an African queen.

All of the Tent City sites are in places where people used to be afraid to venture after dark. Now they have become sanctuaries for healing, reflection, and sharing stories. “Stop the violence!” is the unifying theme, fueled by a universal motivation: “We’re doing this for our children.” Conversations range from grieving over lost loved ones to brainstorming ideas about the root causes of violence and possible solutions. Many Tent City regulars are former drug addicts and “OG’s”, or old gangsters, who have turned their lives around and are now determined to mentor the youth in positive directions. Participants at each site form a microcosm of the entire community, integrating those on solid footing with those floundering on the fringes, struggling to cope with day-to-day existence.

Richmond’s population of around 100,000 is a colorful bouquet of races, ethnicities, and lifestyles. One finds both poverty and affluence flanking a working class core. Home to a multi-billion dollar oil refinery and surrounded by the opulence of the San Francisco Bay Area, Richmond has traditionally been stigmatized by the dominant cultural narrative. Whoever takes the time to get to know the community, however, will soon find a wealth of human spirit that is engaging and infectious.

African Americans were first lured to Richmond in large numbers during WWII for employment in the shipyards and other home-front industries. Since the mid-forties, however, blacks have been pushed to the sidelines by successive waves of institutional racism and structural violence, such as: lingering Jim Crow laws and rampant housing discrimination in the 1940s and 1950s, Cointelpro’s crushing opposition to the blooming black liberation movements in the 1960s and 1970s, the successful efforts by the CIA to flood the nation’s inner cities with cocaine in order to fund their various Central American military campaigns during the 1980s, followed by corporate globalization’s decimation of domestic jobs and local businesses from the 1990s onward. While the Civil Rights movement and its aftermath saw numerous African Americans achieve middle and upper class prosperity, far too many remain plagued by unemployment and despair. That insidious by-product of racism, persistent internalized self-hatred, results all too often in black-on-black crime.

Tent City is an indigenous African American initiative, to which all people are invited. Each site has its own flavor, and all of them exude a welcoming “front porch” feel. Soul food, rhythm and blues, gospel, prayer circles and good-natured ribbing are commonplace. Activities for children include afternoon homework help, Friday night dance contests and weekend art projects. Late one evening, four visitors of Latino, Haitian, Congolese and European-American descent joined Shawn Godfrey, Willie Pearl Thomas, John Wayne Fontenot, Jerry Jefferson and a dozen or so regulars at the North Richmond site as they gathered around the fire. Warm welcomes, conversation, and hugs were exchanged, and before long it was time for “open mic”: host Steffan Cowans made sure everyone present was encouraged to speak to the group and express their feelings about being there. Each person was acknowledged and applauded. Later, the Congolese visitor Jacques Depelchin noted how much the experience reminded him of a “Mbongi”, a traditional African community-based problem solving process that includes everyone, and especially gives voice to those who aren’t usually heard.

While it is still too soon to see their effect in crime statistics, all who have been exposed to the Richmond Tent Cities claim that they are making a difference. “For the first time in years, rival factions from South, Central and North Richmond started a dialogue”, said Rev. Andre Shumake. As nonviolence scholar and UC Berkeley Professor Michael Nagler points out, nonviolence sometimes “succeeds” and always works, meaning that the short-term success is uncertain, but in the long run, nonviolence always changes attitudes, relationships, and situations for the better.

This peace effort certainly seemed to work for one distraught young man who walked up to the fire circle at 41st and Cutting after midnight, lamenting the theft of his vehicle and all of his tools. When he arrived, he was bent on taking revenge on whoever had snatched his livelihood away. The empathetic expressions of those present, along with Ms. Jackie Thompson’s and Ms. Bernice Mulder’s comforting consolations, had a visibly calming effect on him. A woman stepped aside with him into the shadows and said, “It’s okay. We’ll talk.”

Marilyn Langlois and Fred Jackson are Richmond-based community activists and members of Transcend USA.